Wondering why Build SMART is doing so many projects in Pa. for pioneer design/builder Tim McDonald? This is it!

Architect Laura Nettleton is standing in a former classroom in a 120-year-old elementary school that she helped turn into one of the most energy-efficient apartment buildings in Pittsburgh.

She is talking, metaphorically, about coats.

Her coat — stylish and black with wide sleeves and an open collar — is the old way of building: thinly insulated with lots of gaps where air and heat can escape.

A visitor’s down jacket is this renovated school: sealed at the wrists and zipped to the chin, it traps heat without requiring much energy.

“My coat is useless if it’s too cold outside,” she said.

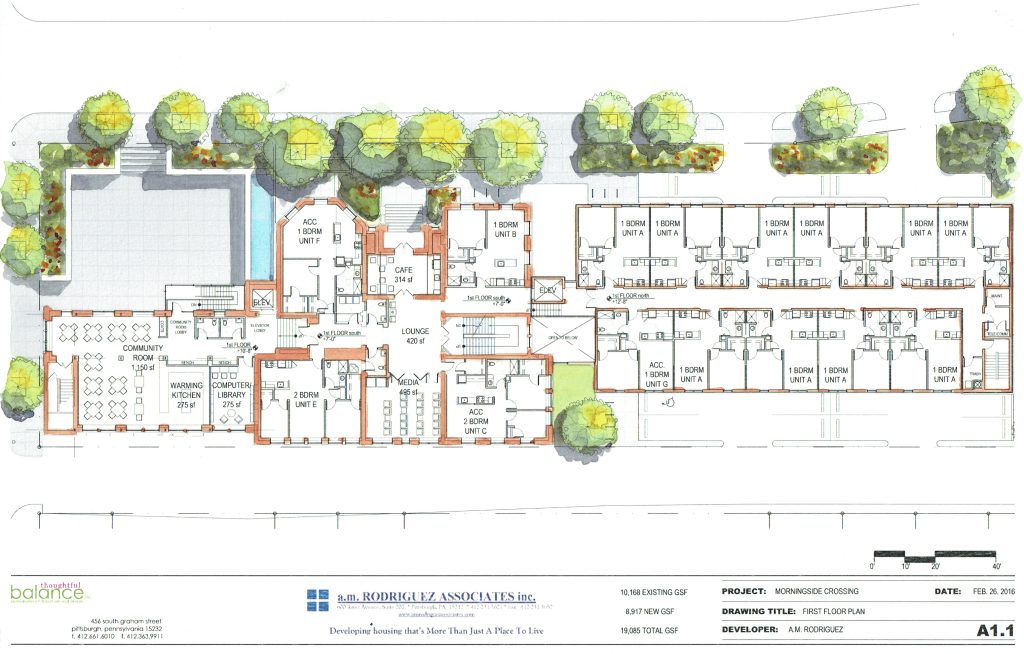

But in this, the puffy coat of buildings — an example of the vanguard of efficient building design known as passive house — it is warm even right next to the tall, triple-paned windows on a chilly November night. The high-ceilinged, two-bedroom apartment for seniors in Morningside has thick insulation and an airtight barrier separating the inner and outer walls.

The 46-unit Morningside Crossing project and 23 other multifamily affordable housing projects in the state are being built to meet ultra-efficiency standards because of an unlikely green building advocate: the Pennsylvania Housing Finance Agency.

The staid state-affiliated agency decides which projects in Pennsylvania earn coveted federal low-income housing tax credits.

In 2014, a change that PHFA made to its competition criteria for the tax credits created a wave of interest in passive house building, and not just in Pennsylvania. It rippled across the country.

Within two years, Pennsylvania went from having just a handful of passive house residential units to having nearly 900 in the works — more than any other state at the time. Since then, 14 other states’ housing finance agencies have followed the PHFA’s model and added passive house to their tax-credit competition. About 16 more are considering it.

“It’s PHFA’s interest and incentive that made this happen,” Ms. Nettleton said.

Craig Stevenson, whose Carnegie-based firm, Auros Group, monitors the performance of energy-efficient buildings — including Morningside Crossing — credited the Pennsylvania Housing Finance Agency with being “a real thought leader.”

“They are revolutionary in the way they are looking at buildings,” he said.

Spreading the idea quickly

Passive house design is based on an intuitive premise: If you insulate a building, meticulously protect against air leaks and take advantage of heat from the sun, you can maintain temperatures by using a small fraction of the energy it takes to heat and cool conventional buildings.

Highly efficient ventilation systems filter and circulate fresh air, often leaving the indoor air healthier to breathe than outdoor air, especially in places with poor air quality, like Pittsburgh.

Philadelphia-based architect Tim McDonald and his firm, Onion Flats, had designed an affordable, passive house project in Philadelphia in 2012 that came in on time and on budget. It was the first certified passive house project in Pennsylvania.

If he could do it, he thought, so could others.

At the time, passive house was a great idea with few adopters. In 2014, there were fewer than 300 certified passive house residential units in North America, according to the Pembina Institute, a Canadian clean energy think tank.

Mr. McDonald wanted to spread passive house design across the industry quickly — not just through one energy-conscious developer or project at a time. Buildings are responsible for more than a third of the country’s energy-related carbon emissions, so reducing their energy demand is a crucial step in addressing climate change.

“How could we transition the industry to a carbon-neutral future at scale?” he said. The affordable housing sector offered a promising path.

Affordable housing tax credits are highly competitive — only a quarter of low-income housing tax credit applications to the PHFA get funding — which pushes developers to come up with innovative ways to keep costs down.

People who build affordable housing also build market-rate housing, so the ideas they learn in one arena can catch on across all building sectors. Plus, affordable housing agencies are interested in energy efficiency as a way to save building owners and low-income residents money.

Mr. McDonald approached the Pennsylvania Housing Finance Agency just as the agency was looking for new ways to encourage developers to improve their buildings’ energy performance.

After establishing criteria that every proposed project must meet, the PHFA creates a menu of optional criteria. If developers include them in their design, they can earn points and increase their chances of getting funding.

Since 2002, the authority has focused on cutting buildings’ energy costs. It began awarding points in the selection criteria for projects that met standards for better insulation, then energy-efficient appliances, then renewable energy.

But the agency found that what starts as an enhanced goal soon “just becomes standard operating principle for the developers,” Stan Salwocki, PHFA’s manager of architecture and engineering, said. “We have raised the bar every few years to make them more energy efficient still.”

In 2014, Mr. McDonald, Ms. Nettleton and about two dozen other representatives involved with building, redevelopment, sustainability and government met with the PHFA to discuss how to incentivize passive house design.

The agency agreed to give 10 points out of a possible 130 points for developers whose affordable housing projects are built to meet passive house standards.

‘It is the free market’

The pushback from the development community was significant.

But the answer was straightforward: If you don’t want to bother with it, you don’t have to take the points.

“It’s not regulation. It’s competition,” Mr. McDonald said. “It is the free market. It’s about nudging the industry to get creative.”

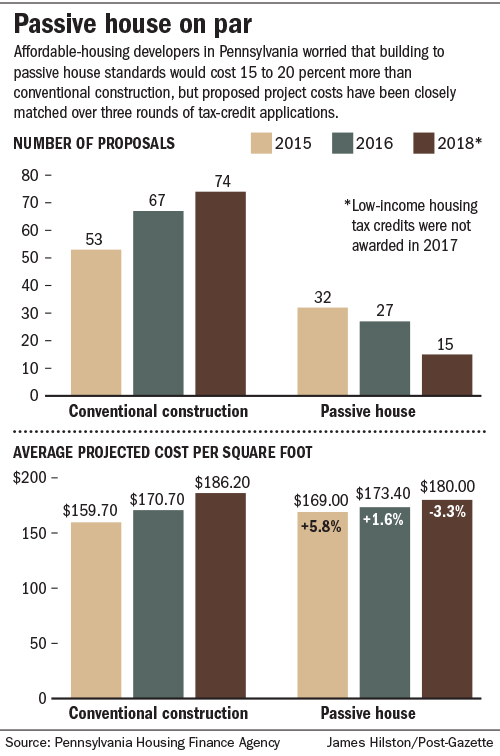

Mr. McDonald said the Pennsylvania Housing Finance Agency expected maybe 5 percent of applicants to go for the passive house points the first year. Instead, 38 percent — 32 out of 85 applicants — proposed passive house projects in 2015. Eight of them received funding.

The next year, 27 out of 94 applications proposed passive house projects and 10 received funding.

Mr. McDonald was elated, but nervous.

Passive house “is not some insanely difficult standard to meet,” he said, but it has to be executed well. If air-sealing is done improperly, buildings can develop issues with moisture buildup and mold.

He told both of the major passive house certification organizations about the PHFA initiative.

“They both were like, ‘This is fantastic!’ And then they were like, ‘This could be really disastrous, because you are setting loose architects and builders and engineers that have never done this before.’”

The passive house consultants on the initial projects worked together and trained each project team to adapt to a different way of building, he said.

Data helped dispatch one early concern — cost.

When passive house points were first added to the competition criteria, developers told the PHFA that meeting the standard would cost 15 percent to 20 percent more than conventional construction.

Instead, passive house projects have been roughly on par with conventional construction, in terms of both the proposed cost per square foot and the difference between a project’s proposed and final costs.

“You really wouldn’t know if it was passive house or conventional,” Holly Glauser, PHFA’s director of development, said. “It’s indistinguishable.”

Tracking energy savings

The Morningside Crossing project won low-income housing tax credits in 2016, the second year of the passive house initiative.

Two-thirds of the project is a retrofit, which poses a particular challenge for achieving the airtightness needed for passive house performance.

One part of the existing school structure — a bland 1929 addition — could be partially demolished and insulated from the outside. “Like putting a sweater right over the building,” Ms. Nettleton said.

But to preserve the handsome masonry exterior of the original 1897 school, it had to be insulated from the inside.

The average multifamily project proposed to the PHFA that year anticipated costs of $171.50 per square foot.

The cost of the Morningside Crossing project was $170 per square foot. And that is before accounting for the energy savings that will add up over the lifetime of the super-efficient building.

Before Morningside Crossing, Ms. Nettleton and her Bloomfield-based firm Thoughtful Balance had redesigned a former YMCA in McKeesport to passive house standards in 2013, when such innovation didn’t earn extra points. The building provides homeless and transitional housing.

“I was trying to save my clients money,” she said. “Their utility bills were $60,000 a year.”

Even though the upgrade added an elevator, continuous ventilation, more lighting, cooking facilities and air conditioning, the redesign cut the building’s energy use by 68 percent.

The cost savings were not equally dramatic because the building’s systems were switched from currently cheap natural gas to more expensive electricity in preparation for possibly adopting rooftop solar panels someday, she said. The cost savings turned out to be around 30 percent.

“No other means could have saved even that much at that time, so it wasn’t a complete loss,” she said, “but it wasn’t as good as I wanted it to be.”

Measuring energy performance is the next test of the PHFA program — and the next hurdle for passive house adoption more broadly.

“If you really want to look at building performance, you need to look at life cycle,” said Mr. Stevenson, whose firm specializes in such monitoring.

The PHFA’s data comparing the initial costs of passive house and conventional construction “demonstrated to the world that it is not a premium anymore,” he said. Information on the buildings’ long-term energy performance could be similarly influential and help building managers understand their buildings and make adjustments.

The PHFA is just starting to gather energy data on the first round of passive house projects, which have been occupied for about a year, but getting access to individual tenants’ utility information can be challenging.

Some passive house projects were Phase Two of conventional projects whose first phase can be used for comparison, Ms. Glauser said. And many of the companies that manage the buildings are collecting data about their tenants’ energy consumption “to see what some of the savings are,” she said.

Interest is still strong. Low-income housing tax credits were not awarded in 2017, but eight of the 35 successful PHFA applications for 2018 were passive house projects.

Soon, the PHFA will have a high-performance building project of its own to study. The agency expects to finish a high-rise additionto its headquarters in Harrisburg next year.

It is designed to be passive house certified.

Original Story By: Laura Legere